Tribes & Tourism (02.03.12)

The ever sensitive subject of tourism inappropriately inter-acting with indigenous tribes has again been highlighted with last week’s report on Peruvian tour operators offering ‘human safaris’ in the Manū Jungle National Park region.

The local indigenous rights organisation Fenamad reports that the Mashco-Piro tribe (click to see film) – one of 15 indigenous groups in Peru who have no regular contact with the outside world – are being targeted by local travel companies offering a chance to see “these un-contacted natives”. Whilst the vast majority of international visitors would agree that tourism should keep a safe distance from such peoples, it is a reminder of how difficult the mix of sustainable tourism to all stakeholders is.

Tour operators and travel companies such as Nomadic Thoughts are arguably the most valuable guardians, offering an essential buffer zone between tourists wishing to explore new frontiers whilst safeguarding both the local environment and people that live there-in. The lure of the tourist dollar is always strong and more often than not the end local stakeholders sees relatively little of the profit.

Our job is to protect the destination as much as fore fill our clients desire to find a new experience.

Visiting Ethiopia recently I saw first hand both ends of the spectrum. My family and I embarked on a remarkable five day trek through the Highlands near Lalibela following a TESFA (Tourism in Ethiopia for Sustainable Future Alternatives) trekking initiative. We benefited from outstanding local guides, staying in pre-set huts that the whole local village community owned. The initiative is designed so that the full share of profits is evenly distributed amongst the local villagers. Aside from visiting one of Africa’s most remarkable landscapes the trek provided us with a fabulous insight into the local community and their way of life. As a visiting UK Tour Operator I was also privileged to be invited into the morning Committee meetings at each camp, as they decided how to divide up and spend the money.

In contrast the Omo Valley region in southern Ethiopia – home to some of continent’s remotest tribes including the Mursi, Suri, Nyangatom, Me’en and Dizi – appears to be witnessing a destructive stampede of 4WD tourist visitors as they try and get that last photo before the tribes frankly disappear. With little planning, local authority protection or sustainability forethought these remarkable people have in many cases almost dumped their thousand year old lifestyle for the sake of a few tourism dollars. Unchartered tourists arrive, tip, photograph and depart all in the space of a few hours.

Try it – Google search ‘Omo Valley tribal photos’ – the images are fantastic.

What is not fantastic is that a percentage of the people you see these photos will be drunk of cheap alcohol by midday. Fast bucks for little effort (who can blame them) and no forward looking investment structure has produced the time honoured ‘curse of alcohol’ to a vulnerable people. A professional photographer I met explained how when you looked behind their huts crates of empty beer bottles were “piled as high as the trees”. When I asked him if he had shot images of this as testimony to the situation today he answer “no, it never crossed my mind .. as my clients [photo libraries] are only interested in tribal shots”.

The race against time to protect these people’s way of life is fast disappearing. The hope is that with a combination of government assistance, local NGOs and the tourism industry a way can be found to engage, benefit and enhance both the tribal peoples and visiting tourists lives.

Two other tribes, not far from Ethiopia, are on Survival International’s endangered list – the Maasai (Kenya & Tanzania) and Bushmen (Central Kalahari). Both are located in the heart of exciting tourism areas and also require assistance in continuing their traditional way of life.

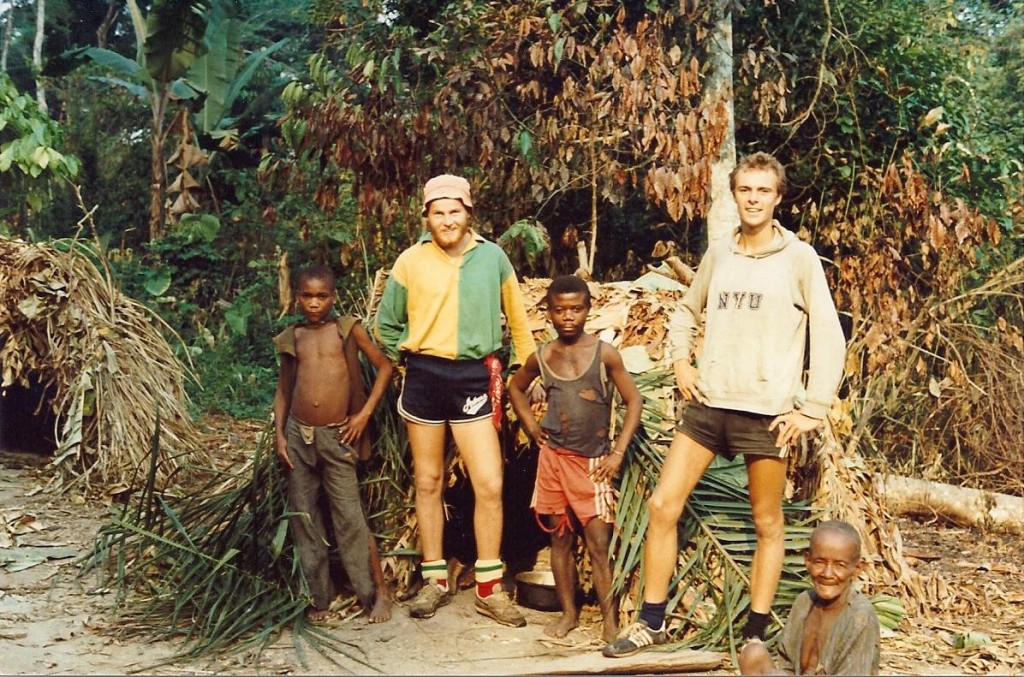

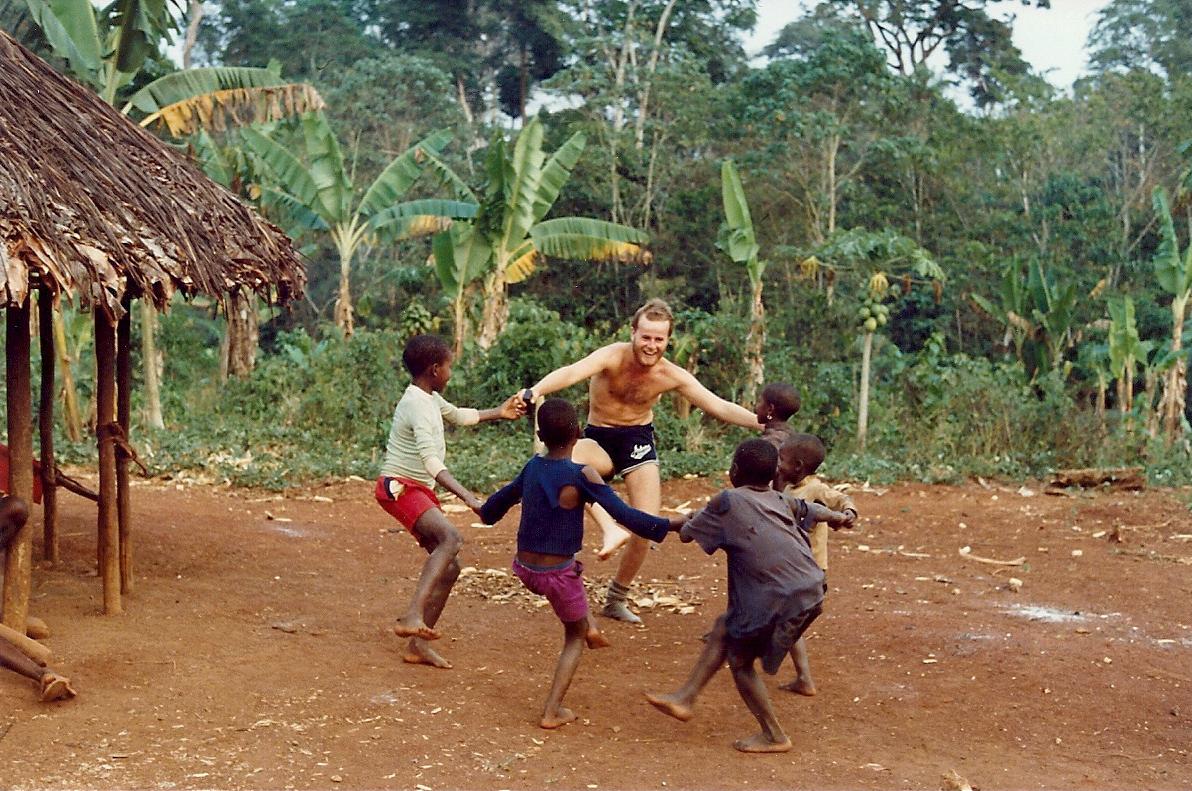

I guess we are all guilty of wanting to discover the unknown – and with the Pygmies (Central Africa) also on that list, I too have to question my own actions – as I have excitedly told many people over the years how special my visit to the Pygmies was in the heart of the Beni Zaire jungle region nearly thirty years ago. At that time the chief of the nomadic pygmy said my friend Moose Bond and I we were the first white people to have visited their jungle.

I often wonder how they are today. Situated in one of the world’s most unstable areas I dare to hope their remote jungle continues to keep them out of harm’s way.