Indigenous Tourism – Hill Tribes of Thailand (27.09.13)

Twenty years ago the UN General Assembly proclaimed 1993 the ‘Year of the World’s Indigenous People’. It also announced that the ‘International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People’ would commence in December 1994.

The delicate question of how best to engage the world’s indigenous people with the rest of society has remained a burning issue ever since. Fortunately the UN’s lead was recognised globally and an additional second International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People started in December 2005.

The 9th August is also celebrated as ‘International Day for the World’s Indigenous People’.

The 9th August is also celebrated as ‘International Day for the World’s Indigenous People’.

Tourism, perhaps more than any other industry, has the ability to engage with indigenous people, and offer opportunities for them to enhance their livelihoods: it can be a force for good in the struggle to safeguard the traditions and way of life of indigenous peoples around the world.

A classic example of how mainstream tourism has developed in such an environment is in northern Thailand. Over the past three or four decades a by-and-large mutually beneficial engagement between the northern cultural minorities and the tourism industry has existed.

As Thailand has developed into one of the world’s biggest tourist destinations (attracting over 22 million last year; Time magazine claimed that Bangkok is the most visited city in the world) the inevitable push to discover, engage and visit one of the most remarkable tribal areas was a pressure cooker ready to blow.

As tour operators we at Nomadic Thoughts have always been aware of how exciting a visit to the northern border tribal regions is, and continue to arrange trips for those so inclined to visit the area.

Managed well, with a true understanding of how some of the most remarkable present-day nomads (originating from various Burma/Tibet/China regions) live in such an area, visitors today can enjoy learning from the hill tribes of northern Thailand, just as I did thirty years ago. In fact I would say that the steady and often difficult development of the Thai-tribal-tourism model has a lot to offer today’s other indigenous communities; the question of whether the Omo Valley tribes in Ethiopia can retain their cultural identity is no less pressing that that of the Yanomami in Brazil or Papuan peoples of Indonesia.

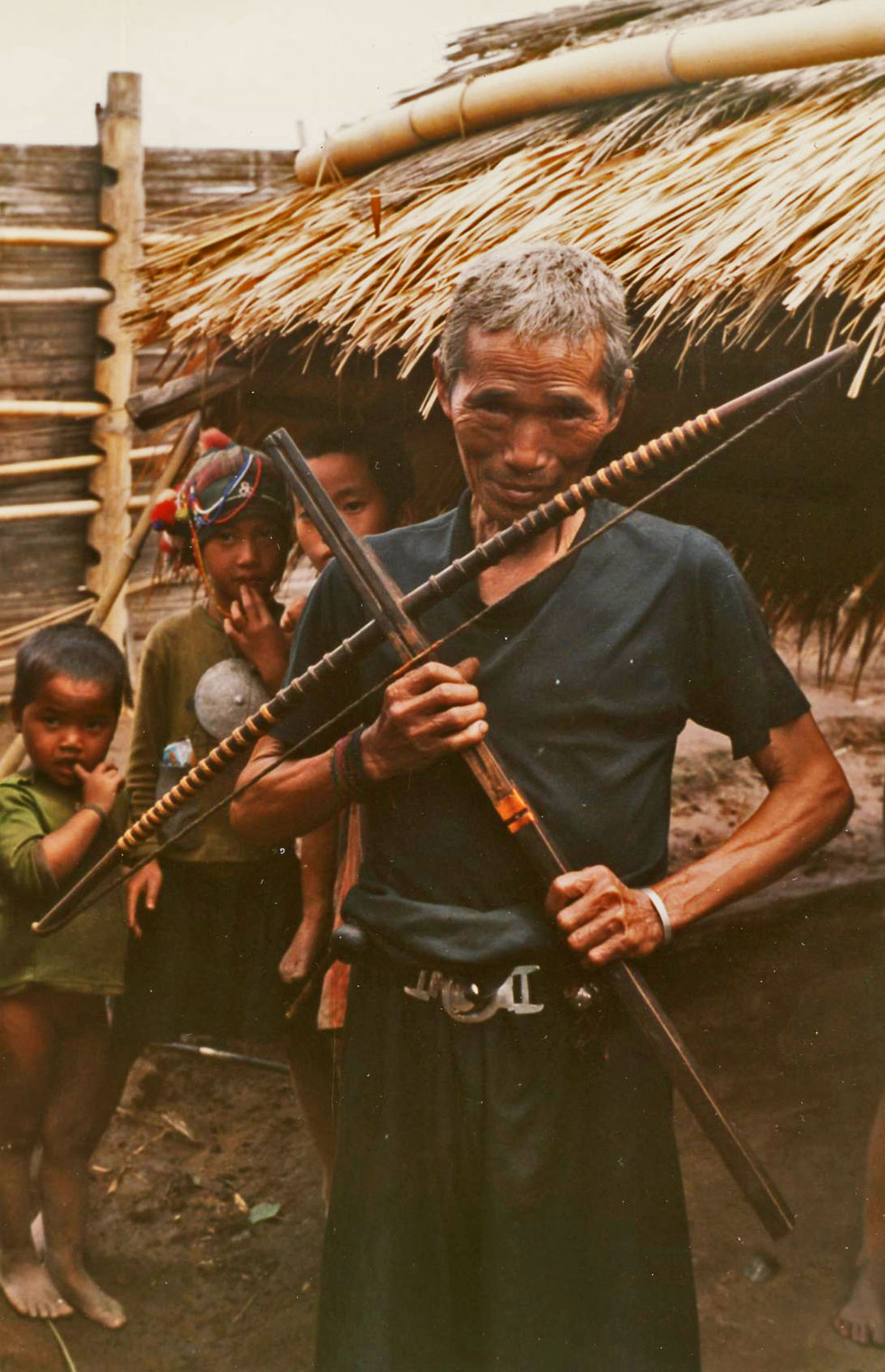

Originally migrating to the Burma, Thailand, Lao border regions over a century ago, there are now seven major tribes – Karen, Meo, Lisu, Lahu, Akha, Yao and Lawa. Each one has a strong and distinct cultural identity, with its own traditional dress, language and customs. I remember being amazed at how walking only a few miles between villages would lead to such a total cultural diversity, with different tribal languages scattered across such a short distance. Indeed, the inhabitants of one village appeared to be unable to communicate with that of another, even though they lived only a few miles apart.

The traditional existence of these hill tribes is through subsistence farming in lush mountainous terrain and often dense forest lands. Luckily for nearly a million hill people in Thailand living on the fringe of society, their fate has been relatively positive with a generally mutual understanding between the state and their traditional way of life. This is sadly in great contrast to their Burmese based tribal cousins who have reportedly suffered appalling human rights abuse at the hands of the military junta.

Tourism, in Thailand’s case, has been instrumental in introducing the outside world to the delicate balance of such tribal community existences. The Pacific Asia Travel Association (PATA), at the end of the last century, commissioned a report on the situation regarding the mountain peoples’ involvement in tourism-related activities.

The year-long PATA project in 1999 canvassed a wide range of tourism stakeholders as well as the tribal communities themselves. The results demonstrated that the mountain villagers themselves valued the economic benefits of tourism to their communities, but were also concerned at how the tribal-Thai-tourism market was developing. For example they felt the training of local tribal guides was as important as securing a plan for the equal distribution of wealth. Survival International, on a broader scale, also continue to champion the cause of tribal peoples.

It does now appear that the future of Thailand’s indigenous hill tribes is a great deal brighter than that of a number of their counterparts elsewhere in South East Asia. Tourism and the freedom to travel to, in and around Thailand has played its part in this. The acid test will be whether the hill tribes themselves are able to manage – along with the tourism industry’s assistance – the balance between sustaining their local way of life, whilst benefiting from those who wish to share, understand and learn from their traditional ways.